Utkarsh Somaiya, Caspar Siegert and Benjamin Kingsmore

Climate change creates material economic and financial risks which central banks need to understand to ensure monetary and financial stability. Their interest in climate change has therefore skyrocketed, with almost one third of central bank speeches in 2023 referencing climate change. Central banks are typically responsible for ensuring monetary and financial stability; these macroeconomic conditions are essential to support an orderly transition to net zero. But central banks are often urged to play a more active role and provide targeted support for the transition. Rather than discussing whether this is consistent with their legal mandates, we ask a more pragmatic question: do central banks have the right tools for this job? We argue that some commonly discussed tools may not be very effective.

We focus on three frequently discussed ways in which central banks might alter the objectives of their existing tools to actively support the transition:

- Greening their collateral frameworks.

- Adjusting capital requirements for commercial banks.

- Lowering interest rates for green lending.

Based on simple calculations, we show the impact of these tools on supporting the transition could be somewhat limited.

To be clear, these tools might still help ensure monetary and financial stability in the face of climate change. However, that’s a separate question. If the goal is to actively incentivise the economy towards net zero, we argue these tools are unlikely to have a significant impact. Central banks with mandates to actively support the transition may consider other tools. For example, working with securities regulators to establish regulatory frameworks to support the sustainable finance market or tilting asset purchases towards greener assets or issuers.

1. Greening central bank collateral frameworks

Central banks lend to commercial banks against collateral. They apply haircuts to this collateral to manage risks. Central banks might ‘green’ their collateral framework by charging higher haircuts on ‘polluting’ (less climate-aligned) assets compared to ‘green’ (more climate-aligned) ones if they deem polluting collateral riskier. They might also increase haircuts beyond what’s necessary from a risk perspective to discourage banks from funding polluting assets. We focus on the second rationale.

Suppose a central bank accepts residential mortgages as collateral and increases the haircut on less energy efficient (polluting) housing by 14 percentage points (pps). This would be big, equivalent to the haircut difference between a safe AAA-rated government bond and a riskier residential mortgage-backed security. As a result, for every £100,000 of ‘polluting’ mortgages commercial banks post as collateral, the central bank would lend them £14,000 less in central bank deposits than if they posted greener mortgages.

We make the conservative assumption that commercial banks recover this lost liquidity by issuing £14,000 of bonds and depositing the proceeds with the central bank. This would cost commercial banks the difference between the interest paid on the bonds and the (typically lower) interest earned on central bank deposits. We estimate this difference to be around 0.35pps.

If commercial banks fully passed on this cost to borrowers of ‘polluting’ mortgages, annual mortgage payments on a 25-year, £300,000 property in the UK that is less climate-aligned would rise by £80. This is about 0.5% of the mortgage’s total annual payments – unlikely to spur homeowners to invest in energy efficiency upgrades and green the housing stock.

2. Adjusting capital requirements

Central banks in charge of bank regulation could also require commercial banks to increase the amount of capital backing polluting assets. For example, by increasing the risk-weights for such assets. If polluting assets face higher credit risks, this extra capital could provide additional buffer against potential losses on these assets.

We consider another rationale, examining whether increasing risk-weights on certain assets could discourage commercial bank lending to ‘polluting’ firms, given that funding a bank via capital is more expensive than funding it via debt. This could be one way of supporting the transition.

Suppose the central bank tries to discourage lending to polluting firms by increasing the risk-weight on such lending from 20% to 150%. This would be equivalent to moving a corporate bond from AAA to a ‘junk’ rating. If risk-weights for polluting loans increase, a bank will need more equity funding relative to debt. Assuming a capital ratio of about 15% of risk-weighted assets, and a cost of equity 10pps higher than debt, the increase in risk-weights would increase the annual cost of funding a £100,000 loan by about £1,800. If this cost is passed on to borrowers, it would increase their interest rate by 1.8pps.

How would this affect the polluting borrower’s incentives? Consider a traditional electric utility company – these firms are highly carbon-intensive and heavily reliant on debt funding. For example, one of the largest electric utilities in the US currently has around £1.5 billion of bank debt. A full pass-through of costs would raise their annual interest expenses by about £26 million. While £26 million is nothing to sneeze at, it’s less than 0.1% of the firm’s revenue.

3. Lower interest rates for green lending

Another tool is for central banks to offer lower interest rates for green projects, such as windfarms. Central banks could lend to commercial banks at favourable rates provided commercial banks lend the funds to green projects. Let’s ignore the difficulties of classifying green projects and suppose the funds are used to develop a windfarm.

Suppose the central bank launches a £1 billion green funding scheme that lends at 2.5pps below the prevailing policy rate (eg 1.5% instead of 4%). We estimate this scheme could fund 1,160 GWh of new energy every year and reduce the cost of each MWh by £14 relative to if this capacity was financed at market rates. This is broadly aligned with recent estimates of how interest rates impact renewable energy.

Unfortunately, discounted central bank lending comes at a cost to the taxpayer. If the central bank lends £1 billion at a 2.5pps discount to its policy rate, this reduces its revenues by £25 million per year. Under reasonable assumptions about loan repayments, central bank revenues would be £235 million lower over the life of the facility. This reduces the financial resources available to the country’s public sector as a whole, reducing funds available to the government to spend on the transition.

How powerful are central bank interventions relative to other factors?

The central bank tools discussed above drive the transition through three different channels: greening the housing stock, increasing costs to polluting corporates, and incentivising clean energy generation. Other policies could also affect these channels or already do so. For example:

- Greening the housing stock: the UK’s Boiler Upgrade Scheme currently provides eligible households an upfront grant of £7,500 to upgrade to a heat pump. While these grants come with fiscal costs, they are probably more effective at greening the housing stock than a central bank intervention that affects annual mortgage costs by £80.

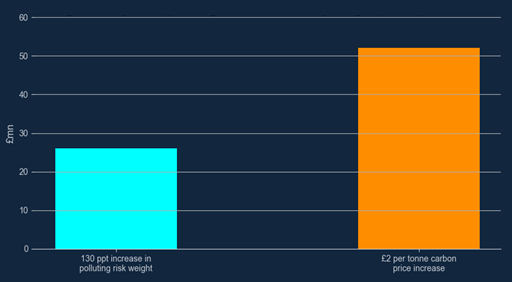

- Increasing polluting corporates’ costs: many polluting companies are subject to Emissions Trading Schemes (ETS) that put a price on the carbon emitted in a given country. The current UK carbon price applied to a companies’ UK emissions is about £40/tonne, but it is significantly lower in other countries. A £2 increase in average global carbon prices would affect an electric utility’s profits about twice as much as the material changes in risk-weights discussed earlier (Chart 1). UK ETS prices regularly fluctuate about £4 per fortnight due to variations in supply and demand.

- Incentivising clean energy generation: direct cash subsidies could also be given to renewable energy providers. In fact, the UK has done something very similar over the past 10 years – the UK’s Contracts for Difference scheme has paid £9 billion to renewable energy providers between its inception and 2024. Directly subsidising 1,160 GWh by £14/MWh would cost around £235 million – exactly the same as the equivalent central bank action we considered above. While central bank action could be effective, it is unclear whether central banks have a comparative advantage in supporting green industries through lower interest rates compared to direct subsidies.

Chart 1: Impact on polluting firm costs from adjusting capital requirements

When actively trying to drive the economy towards net zero, these examples highlight that other policies are likely to be often more effective than the three central bank tools we considered.

Conclusion

Our back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that altering three commonly discussed central banking tools to actively support the transition is unlikely to be particularly effective. Central banks that have a mandate to channel funding towards green projects may want to focus on other policies.

Regardless of these challenges or their mandate, central banks will always need to remain focussed on their core function of delivering monetary and financial stability. By doing so, they can ensure the financial system is strong enough to support the real economy through the transition.

Utkarsh Somaiya and Caspar Siegert work in the Bank’s Financial Risk Management Division and Benjamin Kingsmore works in the Bank’s Cross-cutting Strategy and Emerging Risks Division.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at [email protected] or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied. Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.

Share the post “The right tools for the job? How effectively can central banks support the transition to net zero?”

Publisher: Source link