Jamie Waddell and Danny Walker

Would expanding mortgage supply lead to increased home ownership? Given that 90% of young home owners have a mortgage, it’s tempting to assume the answer is yes. But our analysis suggests that assumption is not necessarily true. We show that increases in mortgage supply have historically had no discernible effect on the home ownership rate and instead tend to push up on house prices, which makes it harder for first-time buyers (FTBs) to afford their first home. They also tend to divert lending towards home-movers and there is some evidence that they increase rents too.

House prices have risen materially since the 2000s but home ownership has flatlined

The average house price in the UK has approximately doubled in the past two decades. Even after the recent bout of high inflation, consumer prices have only risen by three quarters since then, so houses are about a quarter more expensive in real terms. Meanwhile the home ownership rate in England has been flat for a number of years, having fallen slightly following the financial crisis.

It is tempting to think that increasing mortgage supply would increase home ownership

Mortgages are still by far the most common way that young people get on the housing ladder. Half of all home owners have a mortgage in England, but that share rises to 90% among those aged 16–34. So it’s tempting to think that increasing mortgage supply will increase home ownership. While the share of mortgages going to FTBs has risen in recent years, the reduction in overall mortgage market activity means the number of FTB mortgages in the UK has fallen.

The Government has recently asked financial regulators to take action to support home ownership – it is part of the secondary objective given to the Bank’s Financial Policy Committee (FPC). The Financial Conduct Authority recently announced a review of its regulations to support home ownership. One of the measures it is adopting would loosen mortgage credit supply via the rules governing how lenders assess affordability. The FPC separately withdrew its Affordability Test Recommendation in 2022, noting that there might be small benefits for younger and lower-income borrowers, who are more likely to be FTBs.

This begs the question: would increasing mortgage supply increase home ownership in the UK? The answer isn’t clear cut. Increasing credit supply doesn’t necessarily increase the number of FTBs, which would be one of the ways for it to increase home ownership. Previous research looking at housing markets in Ireland, the UK and the United States points to why that might be – higher mortgage supply pushes up house prices, which makes things more difficult for FTBs. In this post we revisit the question.

Isolating the effect of mortgage credit supply rather than demand

To estimate the potential impacts of policies that increase mortgage supply, we need to identify supply shocks in the mortgage market. Doing so means we can strip out factors that increase demand for mortgages that might bias our estimates.

Specifically we look for indicators of credit supply that are unaffected by everything else in the economy. We use a few different measures, borrowing from other research:

- Christie and Rajan (2025) isolate mortgage supply shocks at the lender level by identifying ‘granular’ shocks to large individual lenders in a concentrated market.

- Banks et al (2024) derive a data set of changes in overall credit supply at the lender level, which strips out changes in credit demand.

- Erten et al (2022) show that lenders who were required to ringfence their retail banking operations in 2019 can borrow at lower rates, which would increase the amount of mortgage credit they can supply.

These measures are all at the lender level. We map each of them to Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales and the nine regions of England using the historical shares of lending by each lender in each country or region, which are quite persistent over time. This means we effectively assume that shocks to a given lender will have a larger impact in mortgage markets where that lender has historically had a bigger market share.

Increases in mortgage lending push up on house prices

We run a local projections regression with instrumental variables. That means estimating the effect of the credit supply shocks described above on the value of total mortgage lending in each region or country to isolate the effect of credit supply, then estimating the effect of mortgage lending on the outcomes of interest: the level of house prices and the home ownership rate.

The time period covered by our analysis is 2005 to 2020. The controls in the regression include time fixed effects to capture UK-wide macroeconomic and demographic changes, which absorb the effect of monetary policy on house prices. We also include a set of regional fixed effects to capture persistent differences in the characteristics of regions. We weight the regressions by the number of households in each region.

Chart 1 shows the results. We estimate that a 1% increase in mortgage credit, as a result of credit supply shocks, leads to UK house prices increasing by up to 0.6%. This positive effect on house prices builds slowly, peaks after around one to two years and then might begin to unwind.

Chart 1: Positive shocks to credit supply tend to push up on UK house prices

Notes: The chart shows the estimated impact of credit supply shocks on house prices. Based on a local projection regression of the log of house prices on the log of credit flows, with instruments to identify credit supply shocks, as described above. Controls include time and region fixed effects. Grey area is 95% confidence interval.

Sources: Bank of England, Office for National Statistics (ONS) and Product Sales Database (PSD).

How big is a 1% increase in mortgage credit? The average annual increase before the pandemic was 5% with a lot of quarterly volatility. So it isn’t tiny.

But increases in mortgage lending have no discernible impact on home ownership

Chart 2 presents comparable results for home ownership, focusing on England rather than the UK given data availability. We find no discernible effect of changes in mortgage credit supply on the share of home-owning households (outright or via a mortgage) in a region.

In another specification we find no effect of credit supply on the share of mortgagors in the stock of households. Looking at the flow of mortgages, there is some evidence that credit supply shocks tend to push up on the share of home movers and push down on the share of FTBs. So credit might be diverted away from FTBs, at the margin.

Chart 2: There is no discernible impact of credit supply shocks on home ownership in England

Notes: The chart shows the estimated impact of credit supply shocks on the share of households (level) that are home owners. Based on a local projection regression of the home ownership rate on the log of total credit flows, with instruments to identify credit supply shocks, as described above. Data on home ownership is for England. Controls include time and region fixed effects. Grey area is 95% confidence interval.

Sources: Bank of England, English Housing Survey and PSD.

In a separate analysis using the same methods, we find some evidence that mortgage credit supply pushes up slightly on private rents, but by less than on house prices, so the house price to rent ratio rises.

Why doesn’t mortgage lending increase home ownership?

To understand why changes in mortgage supply affect house prices, it’s helpful to think about how they might affect the demand and supply of housing for owner-occupiers on aggregate. A general theme from the economics literature is that increases in credit supply make it easier for prospective buyers to get a mortgage, raising housing demand.

The effect of this increase in demand depends on how the supply of owner-occupier housing changes in response. At one extreme, if supply can’t increase at all to meet the extra demand, then house prices increase and there is no effect on home ownership. But at the other extreme, if supply responds elastically to meet increased demand, the home ownership rate increases and there is no effect on house prices. Of the two extremes our results suggest the UK housing market is much closer to the first scenario, where supply doesn’t adjust to meet demand.

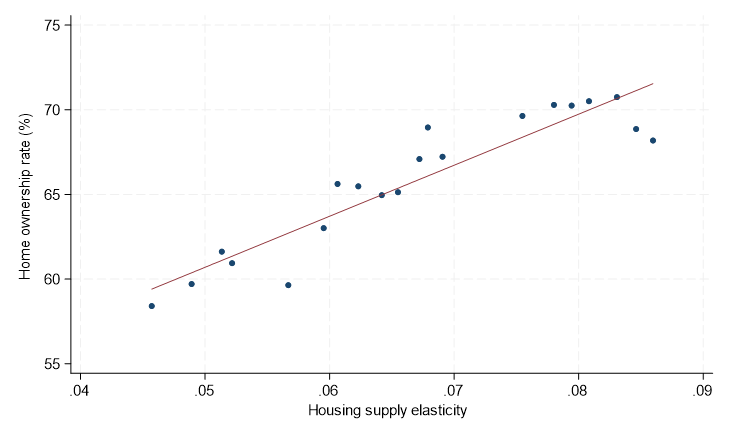

Chart 3: The home ownership rate tends to be higher in regions where housing supply is more elastic

Notes: This binned scatter chart groups Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) estimates for regional housing supply elasticity for regions of England into 20 equal-sized buckets along the x-axis, and for each bucket plots the average home ownership rate along the y-axis after controlling for time fixed effects, house prices, regional GDP, population and total mortgage credit.

Sources: Bank of England, IFS, ONS and PSD.

In reality the impact on home ownership might depend on how targeted the change in mortgage supply is. There is evidence that policies that direct credit specifically towards low-deposit mortgages – which FTBs tend to take out – do increase home ownership. This comes in spite of a large upwards effect on house prices. That might be because those policies redirect mortgage supply rather than increasing it on aggregate.

Supply of housing seems unresponsive to demand

Our results suggest the supply of UK housing is unresponsive to demand but they don’t provide a definitive answer for why that is. New supply could come from newly built houses or from converting rental properties into properties that new home owners want to buy. It could be that owner-occupier and rental markets are segmented, so rental properties are difficult to convert. It could also be that landlords’ perceptions of future cash flows and the quality of the housing stock affect the responsiveness of supply. Other research suggests that the rate of house building is unresponsive to demand in England – so a lack of new houses may well be part of the problem. Chart 3 confirms that in regions of England where house building is more elastic the home ownership rate tends to be higher.

Summing up

Our results suggest that policy actions aiming to increase aggregate mortgage supply might not necessarily increase home ownership, unless they are accompanied by parallel efforts to increase the responsiveness of housing supply. We also shed light on the dynamics of the UK housing market, which are relevant to monetary and prudential policymakers given the importance of housing to monetary transmission and financial sector balance sheets.

Jamie Waddell works in the Bank’s Macro-Financial Risks Division and Danny Walker works in the Bank’s Monetary Policy Transformation Division.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at [email protected] or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied. Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.

Share the post “More mortgage lending might push home ownership further out of reach”

Publisher: Source link