Christoph Herler and Philip Schnattinger

Macroeconomic Environment Theme

The Bank of England Agenda for Research (BEAR) sets the key areas for new research at the Bank over the coming years. This post is an example of issues considered under the Macroeconomic Environment Theme which focuses on the changing infaton dynamics and unfolding structural change faced by monetary policy makers

The recent inflation surge has sparked concerns about how uncertainty over price dynamics shapes households’ financial behaviour. Often, lower uncertainty about inflation coincides with lower expected inflation – when inflation is low and stable, households feel more confident about future trends. In a new paper, Johannes J. Fischer, Christoph Herler and Philip Schnattinger employ a randomised controlled trial (RCT) to disentangle the effects of households’ uncertainty about inflation from the expected level. This disentangling is important: lower expected inflation can discourage immediate spending, while lower inflation uncertainty may push them towards spending more. We show that reduced inflation uncertainty leads to higher planned spending, lower saving rates, and a shift towards liquid assets with fixed returns.

Isolating inflation uncertainty from the expected level of inflation

We conducted an RCT in the March 2024 wave of the Bank of England/NMG Survey of Household Finances – a large, representative survey of approximately 6,000 households in the UK. Using an RCT allows us to disentangle the expected level of inflation (the first moment of the distribution of inflation expectations) from uncertainty about inflation (the second moment). These two moments tend to co-move, making it difficult to separate the effect of inflation uncertainty from the effect of expected inflation on households’ behaviour without this randomised set-up.

After surveying respondents’ prior expected level of inflation and their uncertainty about it, which we measure by fitting a distribution on their responses to a probabilistic survey question, they are randomly allocated into one of four groups. One group serves as a control group, and three groups receive different types of information about professional forecasters’ inflation predictions. The different information treatments are designed to generate exogenous variation in the first and/or second moments of households’ inflation forecasts:

- Treatment Group 1 of respondents receives information about the average one year ahead forecast of inflation (first moment).

- Treatment Group 2 gets informed about the dispersion of professional forecasters’ one year ahead inflation forecasts (second moment).

- Treatment Group 3 receives both pieces of information (joint treatment).

Following the information treatment, respondents are asked about their expected level of inflation and uncertainty again. This allows us to quantify the extent to which they update their prior beliefs about future inflation in response to the different pieces of information. Subsequent survey questions allow us to estimate the causal effect of inflation uncertainty on households’ consumption plans, and follow-up surveys in September 2024 and March 2025 help us investigate how their actual decisions change in response to an exogenous change in inflation uncertainty.

The information treatments reduce households’ uncertainty about inflation

Our information treatments exogenously reduce households’ expected level of inflation and their uncertainty about inflation relative to the control group, as Table A shows. Respondents who receive information about forecasters’ expected level of inflation (treatment Group 1) reduce their expected level of inflation by 0.65 percentage points. Households who are informed about forecasters’ uncertainty about inflation (treatment Group 2) lower their expected level of inflation to a lesser degree, namely by 0.2 percentage points Column 1). As Column 2 shows, our information treatments lead to a relatively smaller change of households’ inflation uncertainty, meaning that respondents’ prior uncertainty about inflation is stickier than their prior expected level of inflation. Chart 1 depicts this, where the distribution of expected inflation shifted more (left panel) than it tightened (right panel) in response to the treatments. This may indicate that the treatments are perceived as less informative about the dispersion of potential inflation outcomes than about the central scenario for inflation.

Table A: Treatment effects on expected level of inflation and inflation uncertainty

Notes: All estimates in this table are obtained using a Huber-robust regression with survey weighted data. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% level, respectively. Standard errors in parentheses.

Sources: Authors’ calculations and Bank of England/NMG Survey of Household Finances.

Chart 1: Density plot of treatment effects

Notes: This chart displays the density of the prior and posterior expected level of inflation (left panel) and inflation uncertainty (right panel) for reach treatment group. Observations are weighted using survey weights.

Sources: Authors’ calculations and Bank of England/NMG Survey of Household Finances.

Lower inflation uncertainty raises households’ planned consumption spending

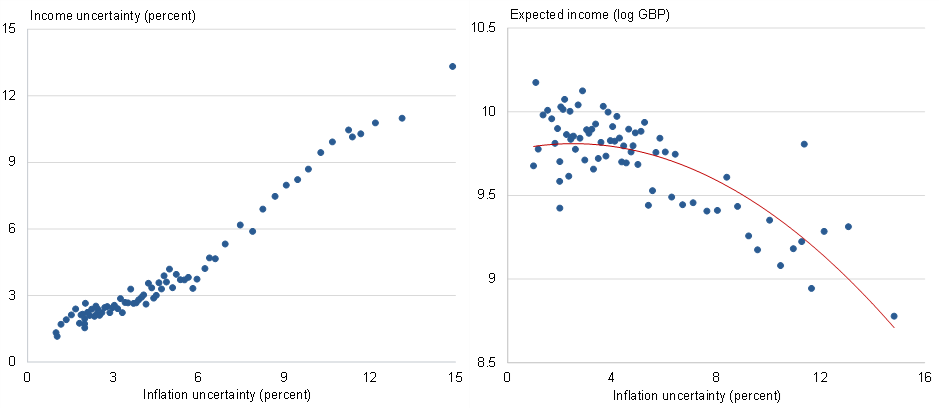

We then proceed to estimating the response of households’ planned consumption spending to this exogenous reduction in inflation uncertainty. Chart 2 depicts the raw negative relationship between households’ reported inflation uncertainty after receiving the information treatment and their planned consumption.

Chart 2: Households’ planned consumption and uncertainty about inflation

Notes: Binned scatterplot shows households’ posterior uncertainty about inflation and their expected annual spending, adjusted for household size.

Sources: Authors’ calculations and Bank of England/NMG Survey of Household Finances.

The results from our empirical estimation indicate that a one percentage point decrease in uncertainty about inflation causes households to increase their planned spending over the following year by around 15 percentage points, as Column 1 in Table B shows. Given the effect of informing households about forecasters’ inflation uncertainty, this implies that our information treatment causes an increase in planned spending of about 2.6%. The effects on planned spending are primarily driven by high-income respondents and households with more liquid assets.

Table B: Effects of inflation uncertainty on spending, saving, and liquid assets

Notes: Column (1) reports respondents’ expected monthly spending in March 2024 for the following 12 months. Columns (2), (3), and (4) report respondents’ monthly spending, the likelihood that respondents report higher monthly savings, and the likelihood that respondents report higher cash deposits six months after the information treatment, respectively. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% level, respectively. Standard errors in parentheses.

Sources: Authors’ calculations and Bank of England/NMG Survey of Household Finances.

Households report lower monthly savings and more liquid assets with fixed returns in follow-up surveys

Approximately 2,300 (2,100) respondents who responded to the March 2024 survey were surveyed again 6 (12) months later. In these follow-up surveys, households report their actual monthly consumption spending, whether their monthly savings have risen, and if their holdings in liquid assets with fixed returns have increased over the past year. These subsequent surveys allow us to estimate the effect of inflation uncertainty on households’ actual behaviour in addition to their expected actions. Lower uncertainty about inflation does not seem to significantly alter households’ reported monthly spending 6 and 12 months after they received the information treatment. This insignificant consumption response is likely due to the considerably smaller sample size and a generally short-lived effect of the information treatment.

However, we observe that a decrease in inflation uncertainty significantly lowers the likelihood that households raise their monthly savings six months after the information intervention. This mirrors the behaviour of euro-area households, but differs from the reaction of US households to inflation uncertainty.

Finally, our results show that lower inflation uncertainty makes it significantly more likely that households report larger cash savings six months after the intervention. This suggests that despite reducing their monthly savings, households adjust their portfolio composition towards a higher share of savings in liquid assets with fixed returns. As the information treatment lowers the expected rate of inflation and the uncertainty about it, the expected real rate of return on these assets increases, whilst the associated risk decreases. A shift into this asset class is therefore consistent with the behaviour of a risk averse investor for whom holding cash becomes less risky compared to other assets.

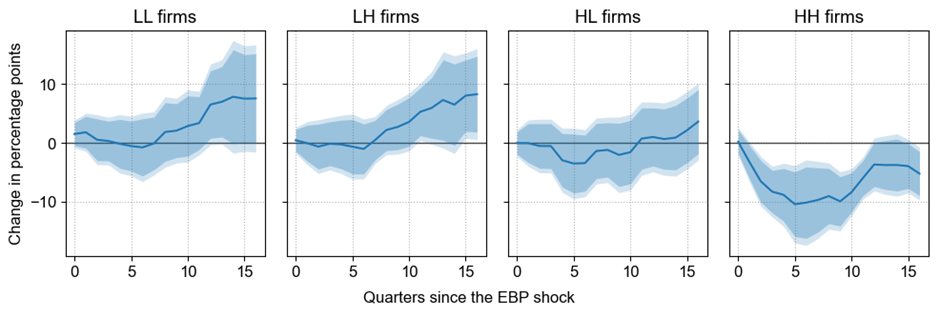

Higher expected income and reduced income uncertainty are driving households’ consumption response

What explains the increase in planned spending and the decrease in monthly savings? Our results show that lower inflation uncertainty raises households’ expected incomes and lowers their uncertainty about future income growth, as the right and left panels of Chart 3 show. However, these two factors cannot fully explain the effect of inflation uncertainty on planned consumption. Even when controlling for expected incomes and income uncertainty (as a proxy for consumption uncertainty), lower inflation uncertainty leads to higher planned consumption spending. The direct positive effect of lower uncertainty on spending combined with the positive correlation between expected inflation and inflation uncertainty is consistent with a supply-side view of inflation, where lower inflation uncertainty is due to reduced uncertainty about adverse supply shocks, or the central bank’s reaction to them. A lower subjective risk of adverse supply shocks lowers inflation expectations and inflation uncertainty, thus reducing households’ precautionary saving motives. In the absence of this precautionary saving channel, households would be expected to smooth consumption over the increase in expected income.

Chart 3: Households’ income uncertainty, expected incomes and inflation uncertainty

Notes: Binned scatterplot in the left panel shows households’ posterior uncertainty about inflation and about their expected income. Binned scatterplot in the right panel shows households’ posterior uncertainty about inflation and their expected annual household income, adjusted for household size.

Sources: Authors’ calculations and Bank of England/NMG Survey of Household Finances.

This supply-side view of inflation has recently been documented. Our results show that this interpretation does not only extend to the expected level of inflation, but also to inflation uncertainty. This salience of supply-driven inflation is perhaps not surprising if households learn based on past experience, given the substantial supply shocks in recent years – most notably those induced by the Covid pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Concluding remarks and policy implications

Our results offer important insights for policymakers. First, by reducing inflation uncertainty, central banks can lower households’ precautionary saving motives and stimulate consumption. Households raise their planned spending in response to lower uncertainty about inflation, because they interpret the decline in inflation uncertainty as an indicator of less adverse supply shocks. This reduces their perceived income risk and prompts them to trim precautionary saving. Second, it can be more challenging for policymakers to influence households’ uncertainty about inflation compared to their expected level of inflation. Even in the controlled environment of an RCT, respondents’ prior beliefs about inflation uncertainty are stickier than their expected level of inflation. Policymakers should therefore take into account the distinct responsiveness and effects of inflation uncertainty when communicating the inflation outlook.

Christoph Herler works in the Bank’s External MPC Unit and Philip Schnattinger works in the Bank’s Structural Economics Division.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at [email protected] or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied. Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.

Share the post “How does lower inflation uncertainty affect households’ financial behaviour?”

Publisher: Source link