Rhiannon Sowerbutts

The Bank of England Agenda for Research (BEAR) sets the key areas for new research at the Bank over the coming years. This post is an example of issues considered under the Financial System Theme which focuses on the shifting landscape and new risks confronting financial policymakers.

Institutions matter. And in the world of economics, few institutions are as prized as independent central banks. Monetary policy independence, many argue, allows central banks to look through electoral cycles to prioritise long-run price stability. But what about price stability’s younger, less glamorous cousin – financial stability? In a recent paper, we develop a measure of regulatory and supervisory independence (or the lack of it) and examine what are the implications for financial stability. Our findings underline the critical importance of robust, independent regulatory frameworks to safeguard financial systems and show that just as with monetary policy – independence matters for regulation and supervision too.

To quote Tobias Adrian – director of the Monetary and Capital markets department at the IMF: price stability is not the only game in town anymore. Since the 2008 crisis, increasing emphasis has been put on financial stability, and the independence of regulators and supervisors to set rules and supervise.

Regulatory and supervisory independence (RSI) is one of the pillars of the Basel Committee’s core principles for banking supervision. But according to the IMF, it is the core principle that has the lowest degree of compliance: 80% of countries have inadequate regulatory and supervisory independence. Weak supervision, and political influence, has been implicated as contributing to several countries’ banking crises including Korea and Japan during the 90s, both of which have seen reforms. And there is already evidence of a political cycle in macroprudential policy: mortgage and consumer credit policies are looser before elections.

So how do we measure regulatory independence and how it changed?

Regulatory and supervisory independence is not binary. We built an index by identifying three main areas of independence that are relevant to banking regulators and supervisors: institutional, regulatory, and budgetary independence (Table A); we build it in a similar way to existing Central Bank Independence indexes for monetary policy but with a focus on regulation and supervision.

Table A: The elements of our Regulatory and Supervisory Independence index

| Institutional | Regulatory | Budgetary |

| • Rules around appointment. • Removal and tenure of head of agency. • Separation from government. |

• Autonomy in setting technical rules for banks. | • Role of elected officials in approving budget. |

We built the index of RSI for 98 countries for the period 1999–2019.

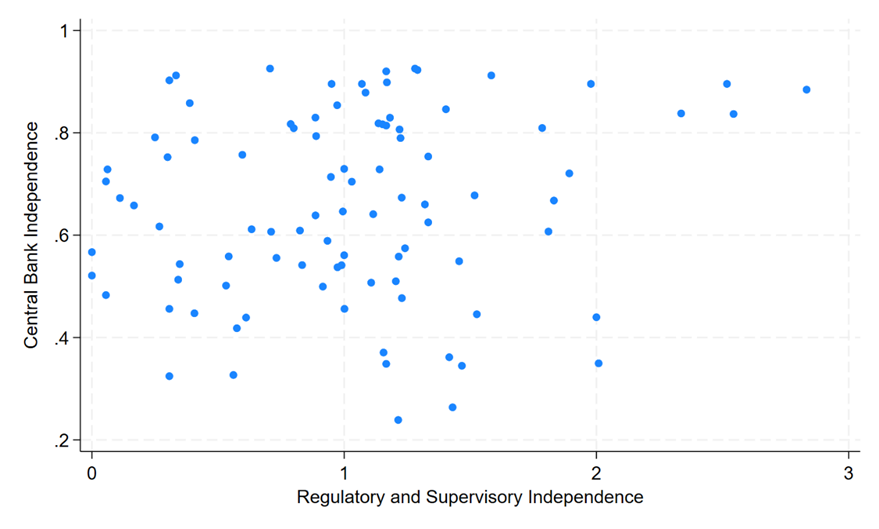

By building this index we can clearly see the difference between regulatory independence and central bank independence. If we look at Chart 1 we can clearly see that some countries have (on average since 1990) highly independent central banks but the supervisor has little independence and vice versa. This is not too surprising: in about a third of countries the central bank is not the supervisory institution, and supervision and monetary policy can be treated differently within the same institution; and speaks to the value of creating a separate index rather than using central bank independence as a proxy. Some studies have used central bank independence as a proxy for regulatory and supervisory independence and these differences were a major motivation for us to build a separate index. There is extensive research on measuring central bank independence (and its associated data). In our paper, we provide more details on the index, including country histories and comparison with other indices.

Chart 1: The relationship between central bank independence and regulatory and supervisory independence (using an average for both indices since 1990)

What is the relationship between regulatory independence and financial stability?

We measure bank non-performing loans (NPLs) as a proxy for banking stability. We chose this indicator as NPLs is an observable and explicit target that supervisors can influence in a bank’s balance sheets.

We use a range of regressions to ask whether regulatory independence improves banking stability (and therefore for most of these countries: financial stability). We examine this over the same period and coverage of our data set 1999–2019 for 98 countries. We use a hierarchical linear model as that allows us to exploit the granular information of bank-level data compared to studies that rely on aggregated data or on traditional fixed effects specifications, but still exploit difference across time and across countries. We need to do this to take into account things like different structures across financial systems – eg more bank based or more market based, or different accounting standards; and we also control for other factors such as GDP and credit growth. On average, we find a one unit increase in the index of supervisory independence is associated with a reduction in NPLs of 0.4 percentage points for a bank in the country where the supervisor operates. That’s good news for financial stability.

When we do the same exercise but replace regulatory independence with a well-used measure of central bank independence, we do not find the same relationship. This is not totally surprising as in many countries the central bank is not the supervisor – but it does highlight the importance of distinguishing between central bank independence and regulatory and supervisory independence.

Can all countries and banks benefit from better regulatory and supervisory independence?

However, we also find that the benefits of regulatory and supervisory independence for financial stability are stronger when the supervisor is the central bank, like in the UK system, whereas they are somewhat more muted when the supervisor is an agency which is separate from the central bank. There are a number of reasons why this might be the case – for example better information on the health of the financial sector – reducing moral hazard when considering use of lender of last resort facilities. But it could also have gone the other way – for example if attention is divided or there are concerns about concentration of power in one institution.

We also examine the impact of different country and bank characteristics on the grounds that some countries and banks may have certain characteristics such as other institutional constraints that make them better able to reap the benefits of regulatory and supervisory independence. For example, regulatory and supervisory independence enables regulators to counteract risky policies, which is especially valuable when political pressures might otherwise encourage short-term, high-risk economic strategies, such as riding a credit boom. We also know that larger banks receive more supervisory attention and that leads to less risky loan portfolios and less sensitivity to industry downturns.

When we examine different country and bank characteristics, we find that the benefits of regulatory independence are fairly universal: for advanced and emerging economies, and for large banks and small banks – regardless of bank ownership, political connections and the market power of the bank.

Do these benefits occur at all times?

These results cover the whole time period from 1999 to 2019. An important question for financial stability is whether the relationship holds during crisis periods as well as normal periods. This question is harder to answer as systemic crises are rarer than ‘good’ times and we are unfortunately unable to conduct an analysis to see whether more independence leads to fewer systemic crises.

We run our estimations again but this time we add measures of systemic banking crisis including bank equity crashes and a database supplied by the IMF. Unsurprisingly NPLs are higher in these periods. But having higher regulatory independence tends to substantially mitigate this effect. In other words: it limits the effect that banking crises have on the decline in credit quality. We think that during a period of turmoil, higher independence can guarantee a more rapid and effective reaction from the supervisors, as it lowers the political frictions they may face. However, these results are less robust than our full sample results.

What next?

This is just an initial step into examining the benefits of regulatory and supervisory independence for financial stability. We would like to see and do more work on the topic:

- Does regulatory and supervisory independence impact other aspects of banking, such as bank lending, profitability, efficiency, or competition?

- Do independent supervisors differ from their more politically dependent peers in the prudential policies and decisions they take?

- And what are the driving forces behind different degrees of independence around the world?

If you’d like to try to answer some of these questions, you can start by reading the longer paper and downloading the database we constructed.

Rhiannon Sowerbutts works in the Bank’s Macroprudential Strategy and Support Division.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at [email protected] or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied. Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.

Share the post “Regulatory independence and financial stability”

Publisher: Source link